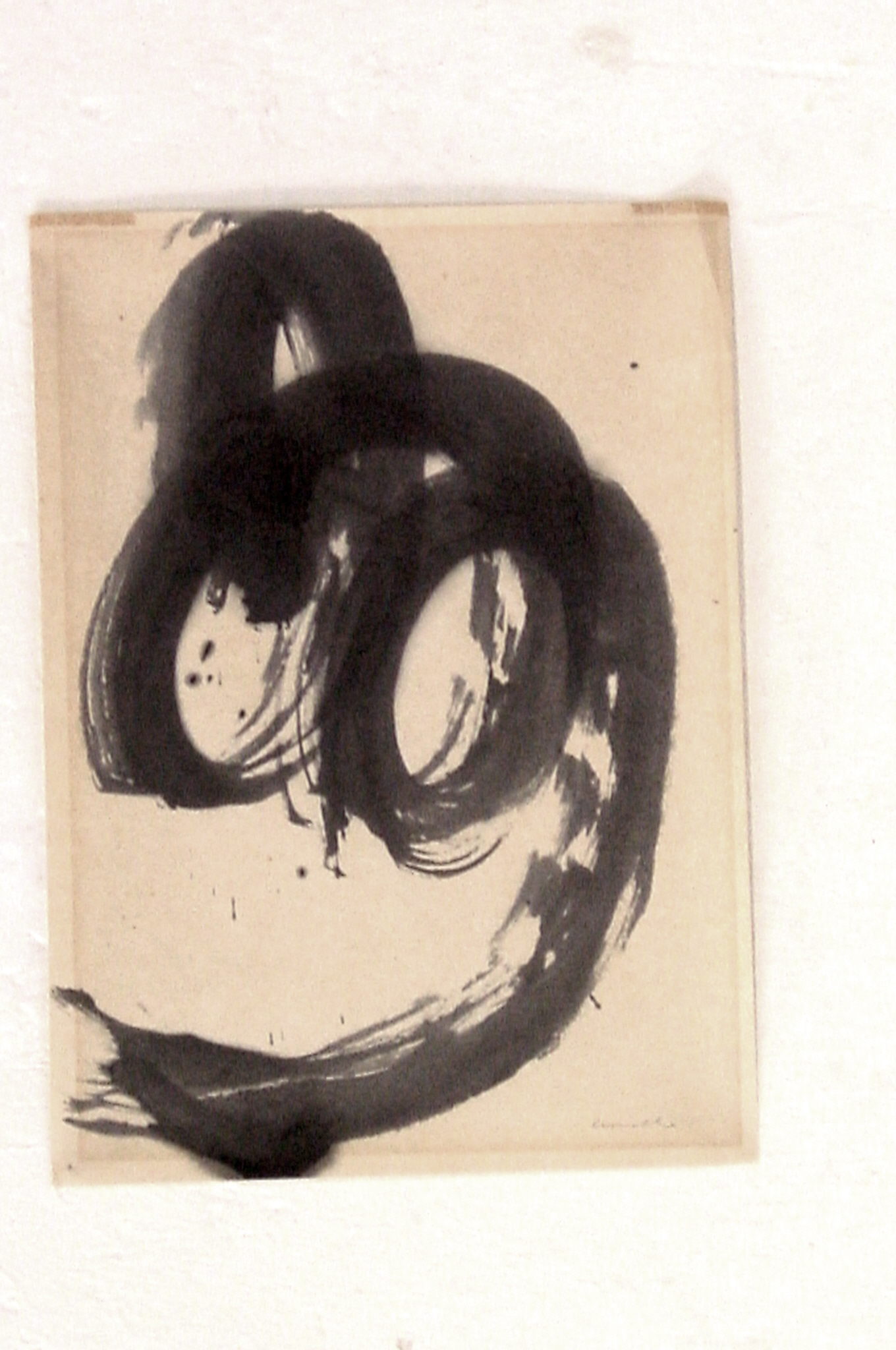

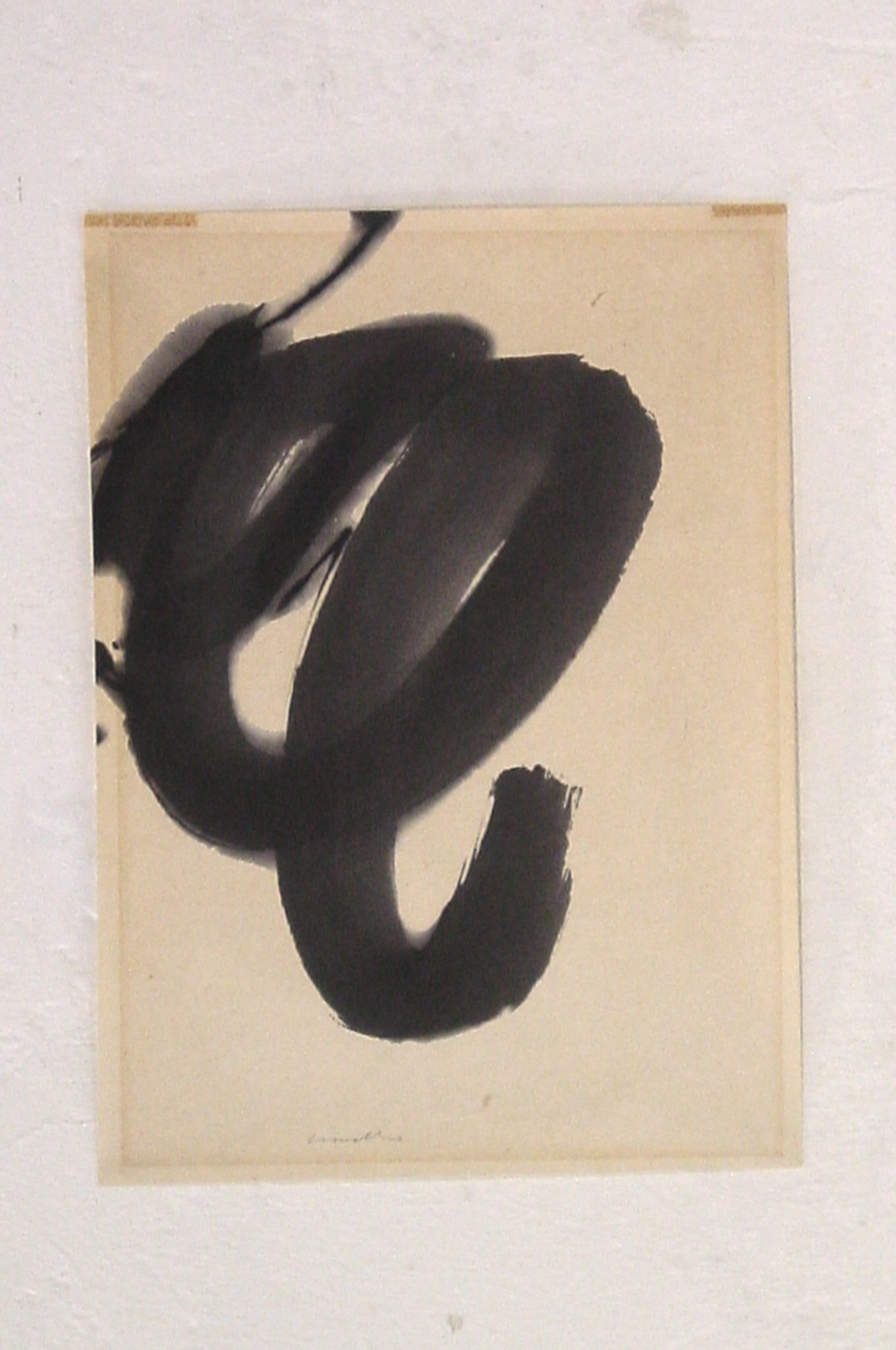

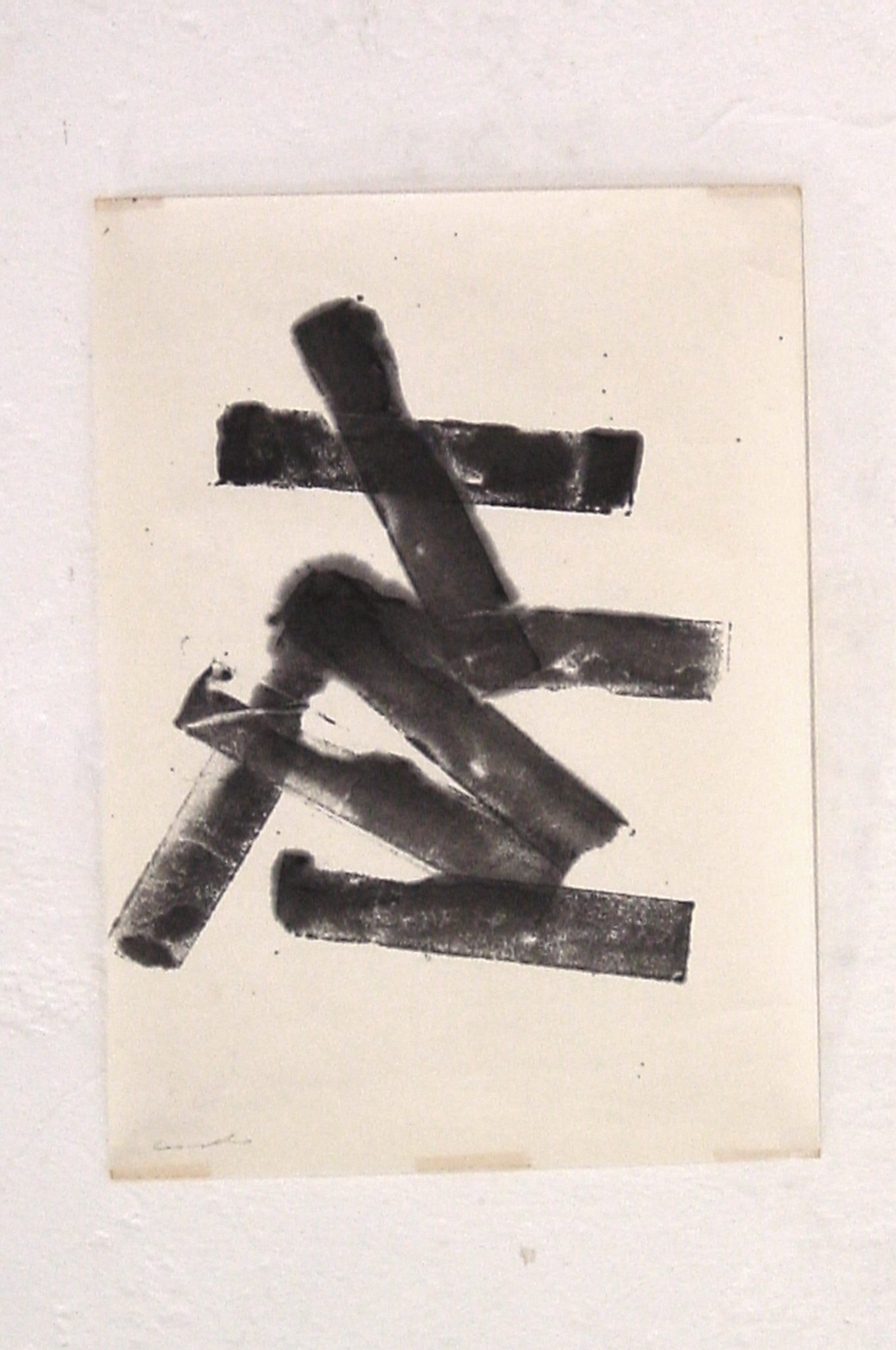

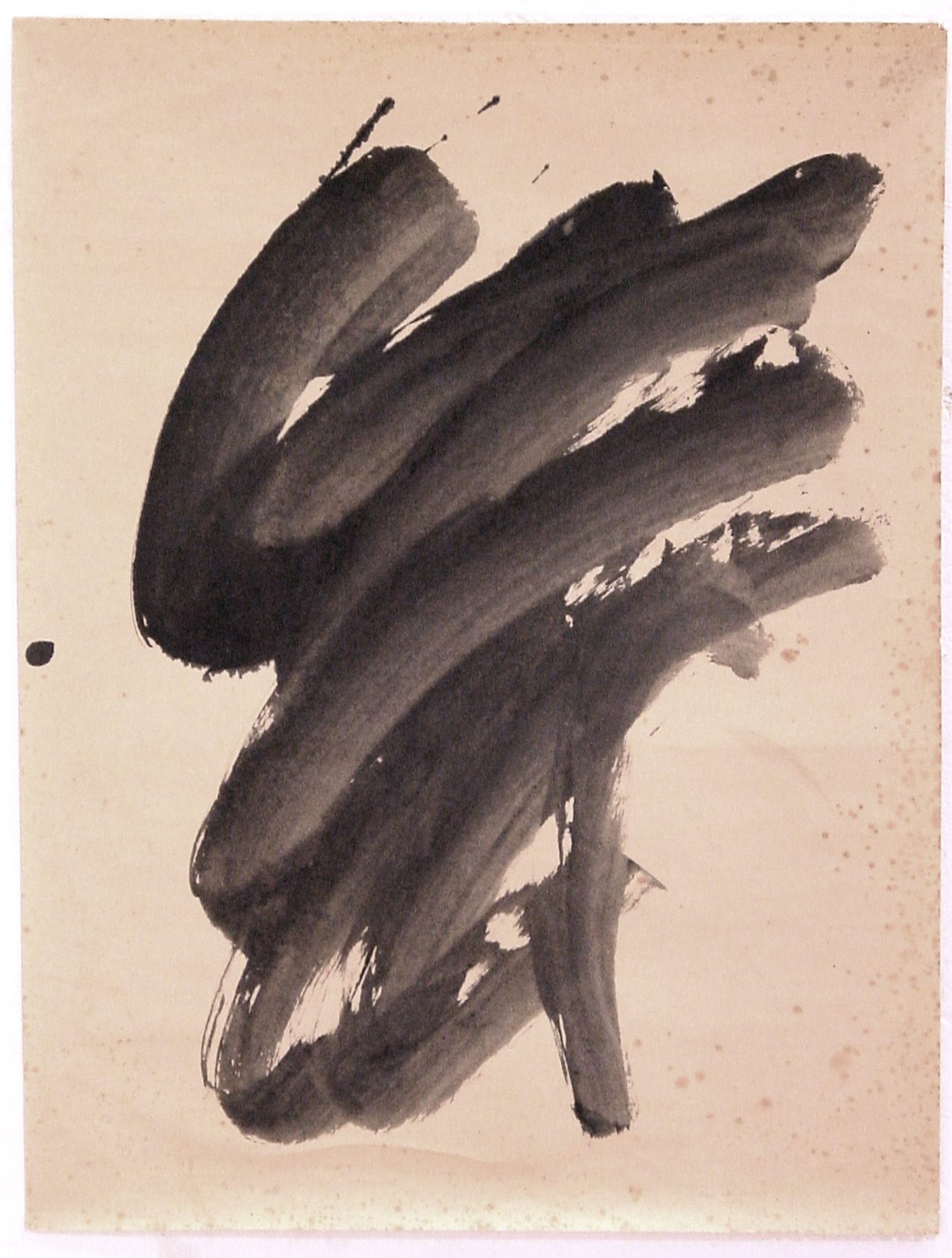

On Calligraphy:

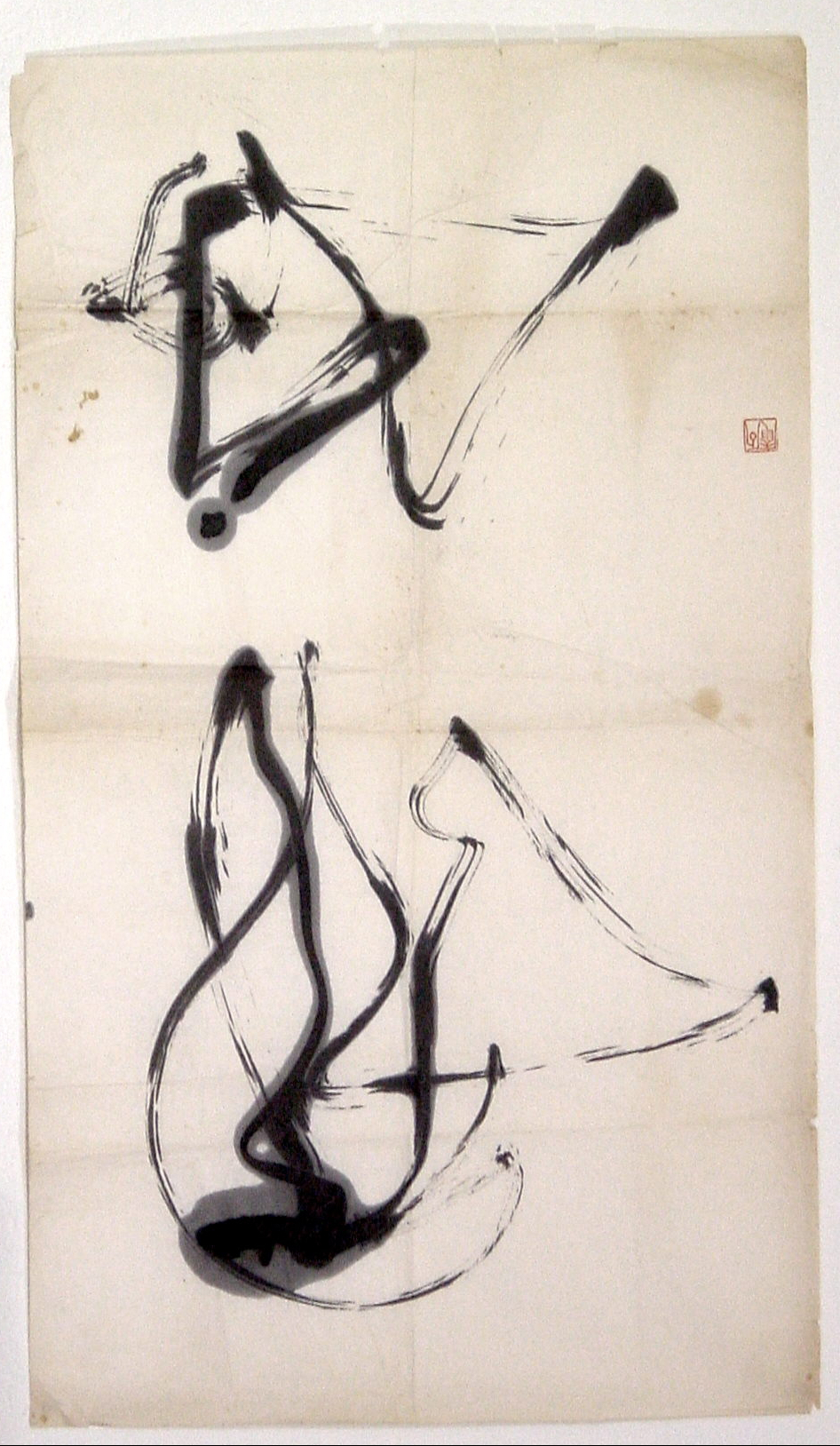

“…But there was one powerful influence which tended always to restrain and purify, and which, though its working is most apparent in pictorial art, has made itself felt in many branches of Japanese life. This art was the practice of calligraphy. No full understanding of Japanese aesthetics can be reached by those who do not appreciate the written characters. They may be the symbols of ideas, but they are not pictures of things; and therefore a man who takes up his brush to trace them is not distracted by any desire to represent or even to suggest a concrete reality, but aims at making shapes whose beauty is their very own and does not depend upon their significance. He moves, as it were, in a world of pure form, and he is concerned only with abstract design.

For him, to write beautifully is to solve certain fundamental problems of art. The line must be unerringly placed, it must be in just relation to its fellows, and though it may pass from strength to softness it may never falter, but must be alive throughout its length. The ink must merge with the soft paper, neither lying inert upon its surface nor spreading aimlessly beneath. The brush, suitably charged, and directed, not as is the pen by a cramped motion of the fingers but by a bold impulse of the whole body transmitted from the shoulder to the wrist, will produce a subtle range of tones between the faintest grey and the deepest black. To a discerning eye such modulations, under the sure touch of a master, can give as profound satisfaction as the most harmonious blend of colour.

In Japan, therefore, calligraphy was not a mere convenient handicraft but an art, the sister and not the handmaid of painting. A skilled calligrapher is already an artist equipped in most essentials, for in learning to write he has undergone a rigorous training in brushwork, in composition, in design, and lastly in speed and certainty of execution, for the nature of his materials will permit of no fumbling hesitation. No wonder, then, that in a society whose outlook on life was almost entirely aesthetic, an art governed by such severe and yet elegant canons should be pre-eminent.

For a Heian courtier to be unable to write well was to be hardly respectable; to have a good hand was to have breeding and taste. Learning in an official, piety in a priest, beauty in a lady of fashion, these scarcely mattered without that indispensable accomplishment. Handwriting was the companion of poetry, and the beauty of a stanza might depend as much upon its script as upon its turn of phrase. Often a verse would be accompanied by a picture suggesting its theme. So far such decorations were slight and fanciful, and the finished expressionism of fine and wash drawings in Chinese ink had yet to be developed. But it was under the inspiration and the discipline of calli- graphy that it later grew to maturity…”

From JAPAN, A Short Cultural History by G.B. Sansom, New York, 1931

Taiun Yanagida – Calligraphy Master and teacher of William Crovello